A lot of folks have been tagging one another with the ten-album challenge, but the accompanying text typically prohibits any commentary. But writing ABOUT music is equally fun—and even more challenging. So I’m posting the album artwork of ten albums that have deeply impacted my life, along with a brief account of how I understand that impact today.

First up, L.L. Cool J’s debut album, Radio (Def Jam, 1985). It was Christmas of 1985 when my grandmother—bless her heart—gave me the Krush Groove soundtrack on cassette. Her modus operandi was to go to the record store, tell someone that her grandson liked “X,” and ask if they had any recommendations. In this case, I’m sure the term she used was “breakdancing.”

Not knowing anything about the film, I looked at the track list and only “All You Can Eat” by the Fat Boys really stood out. But the piece that most caught my attention in the weeks ahead was L.L. Cool J’s “I Can’t Live Without My Radio (short version).” I loved it, and of course my curiosity was piqued: Where was the long version?

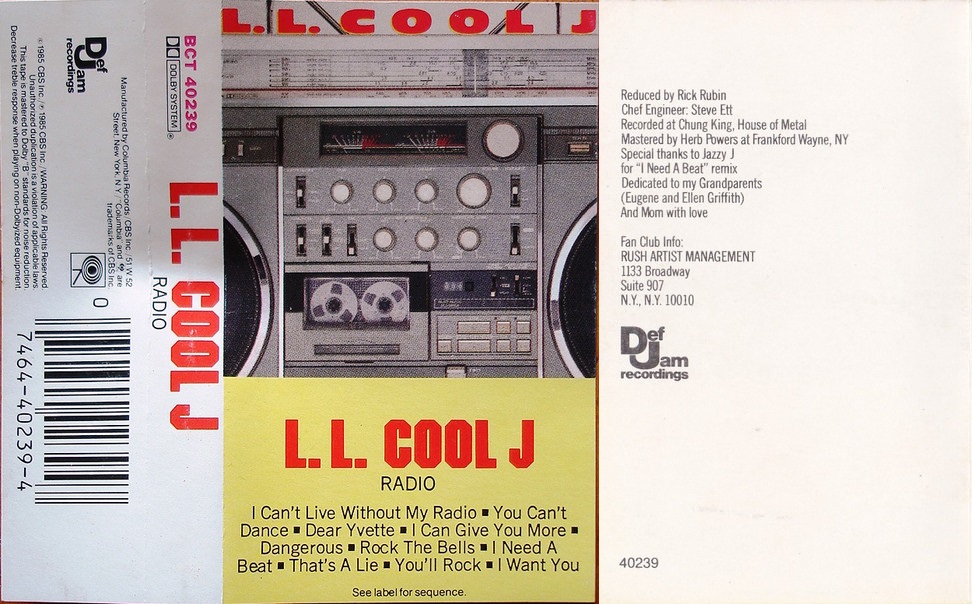

Fast forward to a few months later: I was browsing a flea market with my parents and discovered Radio. There it was, “I Can’t Live Without My Radio,” the first track. I’m pretty sure that this is the first cassette tape that I bought with my own money, though I may also have bought Falco 3 in the same purchase (Amadeus, Amadeus!). Slipping Radio into a portable cassette player on the ride home, I was immediately transported. Every single track had that same raw, barebones, unadulterated feel. It was edgy.

The back of the J-card said, “Reduced by Rick Rubin.” That’s funny, I thought, isn’t the term “produced”? Whatever. Little did I know that it was precisely that “reduction” that would become Rubin’s hallmark style, and that this was, in fact, one of his first productions (along with the Beastie Boys and Run DMC; Slayer would soon follow). Years later some of the top-selling artists—including U2, Johnny Cash, and Metallica—would seek his services in stripping down their styles to their elemental properties.

Of course, at age nine I didn’t yet possess the vocabulary or abstract thought necessary to consider minimalist production values, but sitting in the back of my parent’s Plymouth Volare station wagon, I just knew I loved the sound. Sure, there were lyrics I didn’t understand, but I could at least imagine what this faceless voice was rapping about. (When he belted out “boulevard,” I was convinced that he was talking about Richmond.) Roland Barthes writes about “the grain of the voice,” and it was precisely that grain, the angry rasp of a seventeen-year-old from Queens, that fed my imagination and created an appetite for a world outside my own.

This dynamic, of course, is what motivated the realist novelists of the mid-to-late nineteenth century. With remarkable detail, writers like Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola described a variety of social situations in order to elicit empathy and understanding from their audiences. To be sure, this movement was deservedly challenged in later years as overly sentimentalized. Were readers of nineteenth-century realism really encountering difference? Or just becoming indulgent spectators, like those who picnicked while observing battles from a distance for entertainment?

While such criticism is sound, there is also something to be said for artwork that encourages the expansion of the imagination at least to consider the other. And that encapsulates my encounter with Radio. Was I indulgent? Sure. Was I safely insulated from whatever was encapsulated in the rhyme “My story is rough, my neighborhood is tough”? Absolutely.

But one could argue (and it has been argued, in fact) that the presence of rap and hip hop in the tape players of rural and suburban white kids in the 1980s went a long way in bridging the racial divide in the generation after the Civil Rights Movement. To be sure, there is still much work to be done. But we cannot ignore the positive effect within the imaginations of children that encountering something as different as Radio was for me, hitherto steeped as I was in the voices of the Oak Ridge Boys and the Statler Brothers.

All of which leads me to wonder what “grain of the voice” will make an impact on my own childrens’ imaginations. Will it be something that I share with them? Or must it be something they discover on their own? In any event, I look forward to hearing their Radio.

Debbie Dawson