A lot of folks have been tagging one another with the ten-album challenge, but the accompanying text typically prohibits any commentary. But writing ABOUT music is equally fun—and even more challenging. So I’m posting the album artwork of ten albums that have deeply impacted my life, along with a brief account of how I understand that impact today. I won’t tag others, but I certainly welcome anyone who joins in.

At age thirteen, I was well familiar with heavy metal. Metallica was my world; if I wasn’t listening to one of their first four albums, I was learning to play Cliff Burton’s bass lines by ear. (Of course, I couldn’t figure out any of Jason Newsted’s basslines at that point, because, well, Lars is a jerk.) But a few weeks before my fourteenth birthday, I was on a choir tour with my church youth group. We were headed down to South Carolina to provide Hurricane Hugo flood relief and sing songs about Jesus and sneakers in a different church each evening.

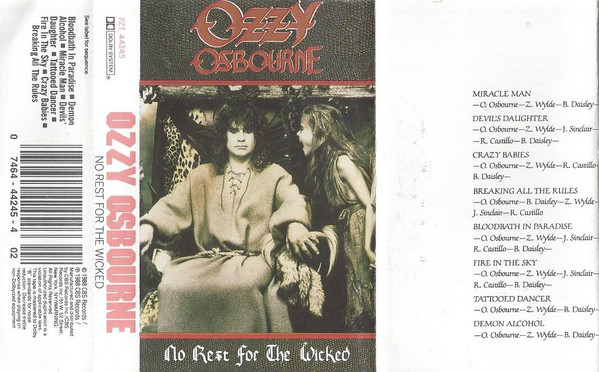

Somewhere along the Virginia-North Carolina border, our caravan of vehicles stopped for gas, and about thirty kids rushed inside for candy and soda. As I passed by the counter, however, my eyes glanced upon a small rack of cassette tapes. Spinning it halfway around, I discovered Ozzy Osbourne’s No Rest for the Wicked (Epic, 1988). It was getting about time to broaden my metal horizons, I figured, so I skipped the sugar and purchased the tape instead.

Climbing back into my mom’s Aerostar with a bunch of adolescents about to get their fix, I peeled off the cellophane wrapping with its “Nice Price” sticker and stuck the tape inside a yellow, waterproof Sony Walkman. And, whoa, were my metal horizons expanded! Within seconds, Zakk Wylde’s riff to “Miracle Man,” with those dizzying vibrato artificial harmonics, opened up a whole new sonic world.

This metal wasn’t angry like Metallica—it was having fun! With or without Ozzy’s (frankly overdone) cackling, the first track itself comprises laughter in musical form. Not a joyous laughter, mind you—more of a spiteful mockery in musical form, but laughter nonetheless. There was something transgressive in that sound, a guilty pleasure with a sense of conscience, but one that was having too much fun to think twice about it.

At the time I didn’t know the specific object of Ozzy’s derision, but the gist of it was clear enough: “Today I saw a miracle man, on TV cryin’ / Such a hypocritical man, born again, dying.” Later, of course, I’d learn that it was all about disgraced televangelist Jimmy Swaggart, who had publicly lambasted the singer for immorality in multiple broadcast sermons. After getting busted for soliciting a prostitute (the first time), however, “little Jimmy sinner” gave Ozzy all he needed for an energetically contemptuous first single on his next album.

I loved the music, but I also wondered about the appropriateness of aurally reveling in Ozzy’s mockery of a fellow Christian. To be sure, I had no fondness for televangelists. By that summer of 1990, the word itself had already taken on connotations of “sleazebucket” and “snake oil salesman.” But here I was, on a musical tour of churches in the Bible belt, and about to enter high school. Questions of ideological identity loomed large, and together music and faith were, for me, the most significant factors in figuring out the answers.

In hindsight, Ozzy (and Zakk) provided me with an important lesson in authenticity, which is a good topic for a teenager to ponder. After all, it is in those teenage years that we define our individuality, searching for who we genuinely are and want to become. But then there are those, like “little Jimmy sinner,” who model hypocrisy and inauthentic living. People like that hurt not just themselves, but all those with whom they are affiliated. So-called “miracle men” had made a mockery of the Christian faith, something that was becoming important to me as that which elicits care for one’s neighbor and those in distress. I was embarrassed, chagrined, by the lyrics of this song, even as I enjoyed them.

In his Massey Lectures delivered just a year later, Charles Taylor argued that the drive for authenticity is at the heart of modern individualism—and is, in fact, one of its few defensible ideals (alongside sincerity). Modernity too easily slides into relativism, narcissism, and libertarianism, but authenticity retains an honest search for truth, goodness, and beauty. It’s the proverbial baby that should not be thrown out with the bathwater.

Crammed in the back of that minivan with sugar-crashed choir colleagues, I knew nothing of Rousseau and Herder and competing theories of modernity. But I could recognize a contrast between authentically listening to the voice within and inauthentically proclaiming moral superiority. And while I didn’t quite enjoy laughing at the revelation of someone’s holiness as a façade, I didn’t feel bad about rocking out to it, either.